Two days before the New Hampshire primary, several New Hampshire voters got a robocall from a voice that sounded like President Joe Biden urging them to stay home on election day with this false statement: “Your vote makes a difference in November, not this Tuesday.” If that seems like a strange message for a sitting president to say, it is because it is. According to the New Hampshire attorney general’s office it had all the hallmarks of what is called deepfake – a message created by artificial intelligence designed to mimic the voice or image of someone without their permission.

That was just one of many similar incidents. Newschecker found that an image circulated by several social media users of President Biden wearing military gear at a national security meeting was AI generated. Deepfakes have recently been created showing Taylor Swift endorsing everything from former President Trump to Le Creuset Dutch ovens.

Photo by Michael Tran/AFP via Getty Images and Shutterstock

A further cause for concern is that some experts believe advances in technology are making deepfakes easier to produce and harder to spot.

So, what can be done about this? How can the public trust that what we’re seeing and hearing is real and true?

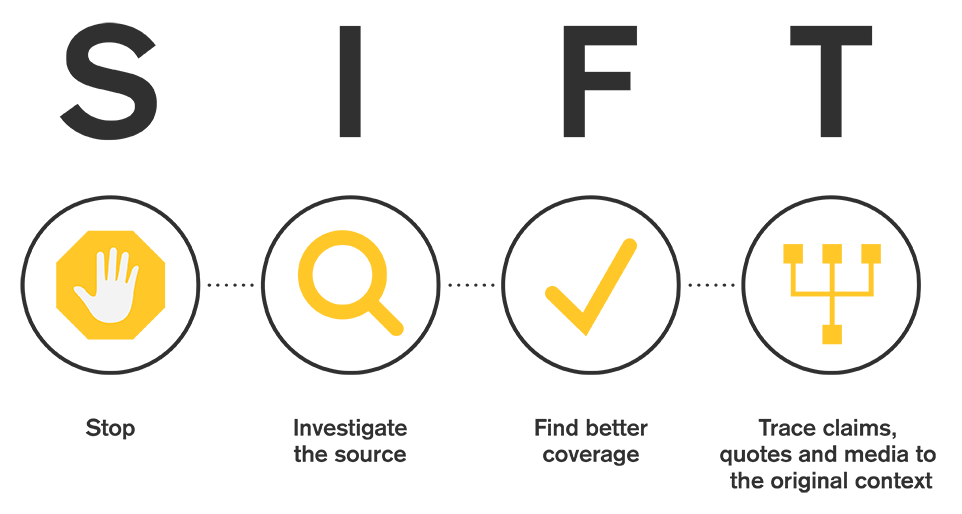

Mike Caufield, a research scientist from the University of Washington, has come up with a great strategy he calls SIFT. It stands for Stop – Investigate the Source – Find better coverage — Trace claims to the original context. In other words, he urges us to be discerning consumers. Think before you believe and, more importantly, before you share. As soon as you see something your gut says is questionable or something that has evoked an emotional response, ask yourself if it makes sense and do a little research to find the source of the image or sound.

Journalists are a great resource for checking deepfakes. Media outlets are being increasingly vigilant about looking for deepfakes with specifically devoted staff. According to Forbes, The Wall Street Journal has nearly two dozen journalists whose sole purpose is to investigate misinformation and deepfakes and The Washington Post has a fake news detection team. In addition, ask yourself if the image or video you are seeing is also being written about in reputable news stories in any way other than to point out that they are fake. Google has a new tool called “About this image,” which is a menu option that allows people to find out when an image was first indexed and what sites it has appeared on since.

Another way is to look for imperfections. NPR analyzed an image that went viral of Pope Francis wearing white puffy coat and pointed out that the rim of his glasses was unrealistic, and his fingers didn’t appear to be grasping the coffee cup in his hand. They also recommend looking for video and audio being out of synch and people using strange posture or facial expressions.

It is encouraging that deepfakes are a subject of conversation because greater public awareness will reduce their power. Plus, it encourages both tech companies and politicians to do something about them. There were two bills introduced in Congress last year, “The Deepfakes Accountability Act” and the “No Fakes Act.” Both would require content labels or permission to use someone’s voice or image. Nine states have laws regulating AI generated content. Although they are not perfect by any means, according to Forbes, X has set up protocols to identify and warn about deepfakes and Meta deletes fake materials when it spots them. More news stories are shedding light on deepfake scams such as warning seniors about the potential of bad actors to fake calls that sound like they are from their grandchildren asking for money after allegedly being kidnapped or arrested.

Being aware is the best defense against deepfakes. Smart consumers who pause before they believe (or share!) what they see and hear will go a long way toward combatting the danger posed by deepfakes.