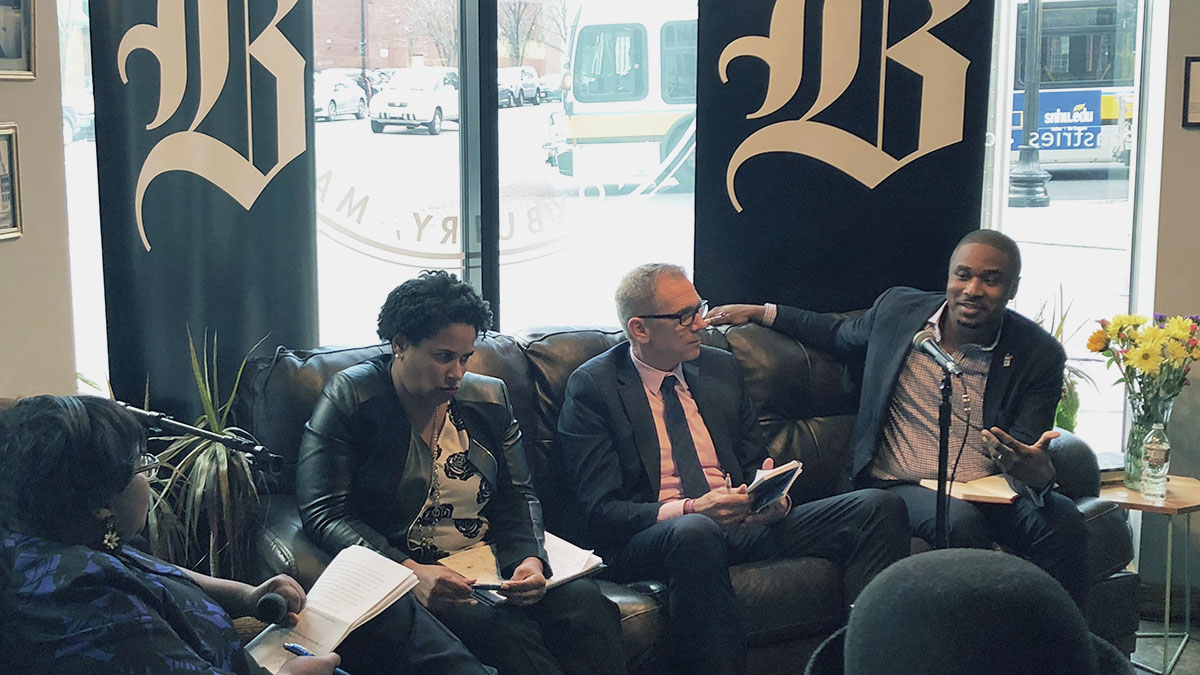

Last week, I attended a Boston Globe sponsored discussion, “Getting Past the Language Barrier to Talk About Race,” which was led by reporter Meghan Irons. We follow her work closely because she writes about issues that are important to our clients, like immigration and race relations.

Mark Culliton, CEO of Teak’s beloved client College Bound Dorchester, was on the panel along with Tanisha Sullivan, the president of the Boston chapter of the NAACP, and Brandon Terry, an incredibly knowledgeable and engaging assistant professor of African American studies at Harvard University.

For 90 minutes, debate about the way in which we appropriately or inappropriately use words when discussing issues of race, and the ways in which these words either propel or hold the movement back, had me at the edge of my seat, quickly scribbling notes.

Take, for example, the currently popular term, “woke.” Terry isn’t a fan. In essence, he explained that understanding the long history of racism in our country and how it manifests in today’s society is not something one can achieve and then claim to have done. He said the concept of being woke, as opposed to not being woke, is faulty because understanding racism is like peeling an onion. It’s an evolving process.

Culliton’s insistence that everyone is a racist, even people of color, evoked a lively discussion that got to the heart of the definition of the term. Could one be racist if she did not have power or authority over others? Sullivan says no. There is a difference between racism and prejudice and we should use the terms with clarity and responsibility, she advised.

All of this got me thinking about how we in PR are accountable for the words we use too. It brought me back to a time in the Eagle-Tribune newsroom when my editor called me out for using the term “pro-life” in a story. Everyone is pro-life, he said. He instructed me to understand the term to be manipulative, used by those who are against legalized abortion to sway others’ thinking. At the Trib, we were not to buy into or encourage the pro-life / pro-choice tag lines. Instead, we were to refer to the two groups more accurately: those who were for, and those who were against, legalized abortion.

Noted. Thank you.

Today, I instruct clients to choose their words carefully too. But, there are times when nonprofits can be too careful, or too politically correct, for their own good.

A client that feeds more children over the summer than any other organization won’t identify the youth they serve as “hungry.” Another client doesn’t want to refer to a neighborhood as “violent,” as if doing so would let the cat out of the bag. Being careful to the point of not being honest or forthright can do a disservice to the cause. If the public doesn’t know what the problem is, why should anyone care about, or help fund, a solution?

These nonprofits aren’t intentionally avoiding the issues; sometimes they just don’t know how to be direct without being accusatory or adding to a stereotype. Or, they worry too much about what other people will say. In short, their desire to do the right thing can create fear that is debilitating when it comes to effective messaging.

There is a difference between allowing fear to enter into one’s messaging strategy and being responsible with words. The former is counterproductive. The latter is wise.