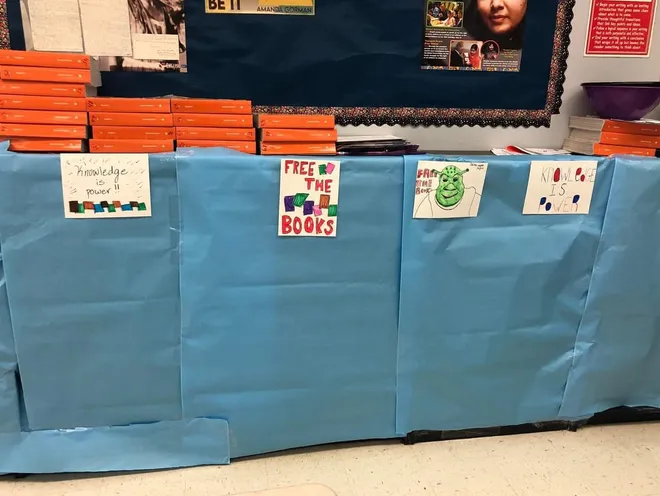

As a big believer in the power of books, I was sickened by the sight of shelves in a Manatee County Florida classroom covered with paper. A school board edict was issued in response to Florida state law HB 1467. It stipulates that all classroom books must be approved by a media specialist who has been specially trained to evaluate them to make sure they are not pornography, are appropriate for the age level and group, and don’t include “unsolicited theories that may lead to student indoctrination.” What makes someone qualified to determine what is indoctrination and what is age appropriate? The criteria for assigning value to books are subjective and suspect. While the wording about which books are in and which are out is vague, the language about the consequences is not. Any violations would be considered a third-degree felony. Other examples of third degree felonies are aggravated stalking, battery of an officer, and grand theft. Seeing rows of empty classroom shelves should raise alarms because books lead kids to ask questions. Blocking certain topics will eliminate those questions and therefore diminish the possibility of having meaningful discussions about critical issues.

Similarly, the College Board made changes to the curriculum of an AP course on African American studies after Republican Florida Governor Ron DeSantis complained about the course, saying it “lacks educational value” . According to the New York Times, the College Board followed DeSantis’ lead and removed writers and scholars associated with critical race theory, Black Queer studies and Black feminism. Prior to the decision, Illinois Governor J. B. Pritzker, a Democrat, sent a letter to the College Board that sets the curriculum to insist Black Queer studies be kept in the AP syllabus. Who should decide? Rejecting or keeping the class and some of the lessons in it will shape what students learn.

Apparently, the desire to eliminate challenging conversations is bipartisan. Stanford University recently took down their Elimination of Harmful Language Initiative’s website after it was criticized for encouraging people to avoid words like “American” (they preferred U.S. Citizen so it doesn’t appear like the U.S. is the most important country in the Americas), “white paper” because it links the color white with something good, and “trigger warning” due to the stress it may cause. While some words should absolutely be avoided (such as the n-word), labeling too many words as harmful implies malicious intent where there may not be any. The current climate of political correctness on many college campuses has made some students and professors feel like they can’t express their opinions for fear of being cancelled, fired (in the case of professors) or labeled racist, antisemitic, or homophobic. This discourages discourse, which is part of what college is all about.

Allowing politicians, parents, and anonymous people on social media to shape education and determine which words are not allowed is a slippery slope. Problems are not solved by ignoring them and pretending they don’t exist. One of the most inspiring parts of working at Teak is witnessing the bravery of our clients who are taking on issues that people would rather not talk about. They confront tough questions like what makes someone join a gang; why can’t some people afford to eat, why do men of color sometimes struggle to finish college; and why indigenous people illegally log in the rainforest? Exploring these questions has led them to create innovative solutions that can be an important part of solving the problems we face.

Education must include content that makes people feel uncomfortable. Last week 93-year-old Holocaust survivor David Schaecter answered 1,000 questions about losing his family and the atrocities he witnessed so that his holographic-like image can be used to communicate with future visitors to the Boston Holocaust Museum, which is due to open in the fall of 2025. What if stories like his were silenced because they may make someone feel bad? Not knowing these stories fuels deniers and raises the risk of something like the Holocaust happening again.

As anyone who ever attended a Thanksgiving dinner with relatives on different sides of the political spectrum can attest – awkward conversations about controversial topics are not fun. They evoke emotions. They have the potential for hurt and embarrassment. But that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t have them. The act of defending an opinion forces us to have facts to back up what we say and listening to another person’s opinion opens us up to the possibility of seeing the issue in a new way. Having difficult conversations helps us confront our fears, form educated opinions that consider many sides, and take action to fix what is wrong with our world.